This week’s substack is going to be shorter than usual because I’ve been out west all week. I’m on the board of a small press in New Mexico and we just published the first book with which I was personally involved, a little. The author, John Fayhee, is one of the great Colorado outdoors writers, a wry funny raconteur of the Mountain West, and I hope you will hit the links below to have a look at his work and perhaps even buy a copy.

Today, the 22d anniversary of 9/11, I am looking out a window onto a yellow field that stretches to the shadows of the San Juan Mountains, outside Durango. The sky is a bit cloudier than it was on that crystalline September morning in New York, when I and a friend stood before CNN watching the towers collapse in real time, while our one and two year old sons played on the floor. That day was a hinge, a pivot, portal to their - our children's - future, closing our past. An editor asked me to write about it that week, and I did, but I wrote that there was not much to say, the meaning was still to come. People are still grappling to express it. One of my graduate journalism students at NYU was four when the planes hit. Gabriella Ferrigine grappled last semester to write a long feature about her mother’s experience on that day (she was just back in the financial district from maternity leave and survived). The New York Times published her essay yesterday, and I recommend it, link below.

Our peregrinations this week have taken us from Albuquerque south to Hatch (green chiles are roasting) to Silver City and the Gila National Forest, then north along the eastern edge of New Mexico, through tiny towns with a few trucks, gas station, and maybe not much else. At one, there was a sign in the diner window with the words Dollar General, and a slash through it. Very few Trump signs along the road. Happy cows. Spectacular vistas. The range where never is heard a discouraging word, and the skies are not cloudy all day.

All-American beauty that can make you weep.

We parked in the searing noon sun at the El Malpais National Monument, and took a short walk over to a massive sandstone arch. When we returned to the car, we learned you can reheat last night’s pizza on the dashboard quite nicely. We also hiked out into the burning, strange lunar landscape of the Bisti Badlands, an eroded sedimentary basin exposing the largest Cretaceous-Paleogene fossil bed in the world.

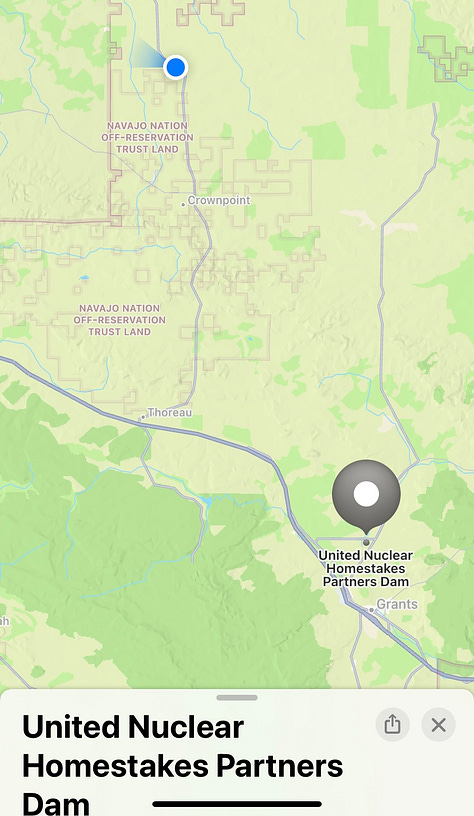

Farther north, we passed through the Grants Mining District, a capital of the American uranium mining industry. During the Cold War, from roughly the late 1940s to the late 1990s, Navajo miners were hired to excavate the deadly mineral that helped the United States maintain its position as Leader of the Free world against the Soviets, who were stockpiling the same weapons at the same rate and probably doing similar damage to their environment. By 1989, the world nuclear stockpile was at 70,300 weapons. (Read Eric Schlosser’s book Command and Control about the accidents and near disasters and you will, if you are an atheist like me, wonder if there really aren’t supernatural beings protecting the human race from its folly).

The uranium miners died slow deaths of cancer. Many are still being sickened by the pollution. I’ve been told the tribes call this area The Land Without Grandfathers. The region is polluted with “mill tailings,” radioactive processing waste, undeclared but de facto Superfund-level disaster areas. Since Russia invaded Ukraine, there are plans afoot to ramp up American uranium mining. Biden recently declared a national monument around the Grand Canyon, which would bar uranium mining, but no one believes the industry will be much deterred from the greater Colorado Plateau area.

When the Grants Mining began, atomic bombs had already been built and dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, using uranium mined in Colorado (in another still-polluted ghost town, Uravan).

Everyone of us born after 1943 has in our cultural DNA something new to the human race. People who came before us might have suspected it, but we know we can destroy ourselves, as a species. In fact, we are in the process of doing so, without the help of the bomb. Our 2023 summer of global burning and flooding is hardly the last.

Today the spectacle of 9/11 is on television and online, as annually it is. The lasting effects of the attack on survivors, and on people not just here but across the planet, are private, personal, hundreds of millions of individual stories that we will never read or hear. We can only gawp at the numbers. America spent $4 to $6 trillion waging wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The wider effect of the wars on terror destabilized a whole region and provoked an estimated 38 million people to become refugees from violence and scarcity. After the Adriana capsized in the Med this summer, pitched more than 700 men women and children to the bottom f the sea, the Nation summed up 9/11’s effect on migration.

America’s forever wars, the series of military operations that began with our 2001 invasion of Afghanistan (which ended up involving us in air strikes and other military activities in neighboring Pakistan as well) and the similarly disastrous invasion of Iraq in 2003. It would, in the end, metastasize into fighting, training foreign militaries, and intelligence operations in some 85 countries, including each of the countries the Adriana’s passengers hailed from. All in all, the Costs of War Project estimates that the war on terror has led to the displacement of at least 38 million people, many of whom fled for their lives as fighting consumed their worlds.

Today is a good day to consider the cost of empire, amid the ashes of the still-reconfiguring world order.

RELATED LINKS

Grand Canyon uranium mining

EPA uranium mill tailings brochure

Wars one terror and mass migration

Fayhee book A Long Tangent

Command and Control by Eric Schlosser

I always have an odd and sad feeling on 9/11. My daughter, now the senior forensic pathologist in the Manhattan OCME, was a 4th year medical student when a doc in her apartment in Brooklyn phoned and asked if she would go with her to the twin towers. She had a police escort. Without thinking what was involved, she said yes. Mercifully, she was removed after four days -- so no illness befell her later on. Of course there was nothing to do, medically, so for four days her job was to help the firemen on breaks rinse their eyes. (Being a dog person, she tried to cheer up the sniffer dogs, depressed because they couldn't do their jobs. The way she did this was to inveigle one of "her" firemen to play dead so the dog could feel he'd accomplished something. She went to reunions of first responders for five years, until she could no more deal with the emotions. Although she'd not yet graduated, I knew, then, she was a real doctor.

Knowing the reverberations will continue..